Better record-keeping isn’t glamorous, but it’s an incredibly effective public health intervention

Treating a broken arm does not generally require an extensive knowledge of the patient’s medical history. But when it comes to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes, that knowledge is crucial.

NCDs are the leading cause of death in Pacific Island countries, accounting for between 60 and 80% of mortalities. In countries such as Fiji and Samoa, diabetes is the leading cause of disability. Lower limb amputation for diabetic gangrene is the most common surgical operation in Fiji, a stat that could be reduced by earlier detection and more consistent treatment plans.

A consistent treatment plan improves outcomes for NCDs such as diabetes

In simple terms, to manage diabetes you need to keep a person’s blood sugar low over the long term. That’s hard to achieve even in the most well-resourced settings, but what really sets it back is arbitrary changes to a person’s eating plan or drug regimen.

In order to know whether a new treatment is working, you need to know whether their fasting blood sugar is improving or getting worse. If you don’t have a person’s medical history, and they return a high blood sugar reading, you might be inclined to think a drastically new treatment is required. But if you had a record of previous tests, and know that their blood sugar is actually improving, then you’d keep the drug the same and maybe make small tweaks to the dosage.

On the other hand, a mildly high reading could be a real concern if that person has never had elevated blood sugar reading before. You would want to monitor the situation closely. If you didn’t know their medical history, you might miss the early warning signs.

Paper-based record systems are an obstacle to proactive healthcare interventions

Paper-based record systems are almost always tied to a single location. If a person’s only interaction with the healthcare system is with a single clinic, that might not cause any issues. That situation, however, would not be likely or desirable. Paper-based records can be put into the hands of patients, of course, but these are too easily lost or damaged and patients may not have access to these paper records when they are at their most vulnerable (such as when they’re going through an emergency medical situation).

Health care in the Pacific Islands – like in many settings – is typically reactive: a person has a specific concern about their health, so they visit a health facility and are treated for that concern. This is a big problem when it comes to NCDs, because these isolated visits can be siloed from each other and knowledge about the patient doesn’t build up – it’s often not until very late in a disease’s progression that you notice its insidious effects.

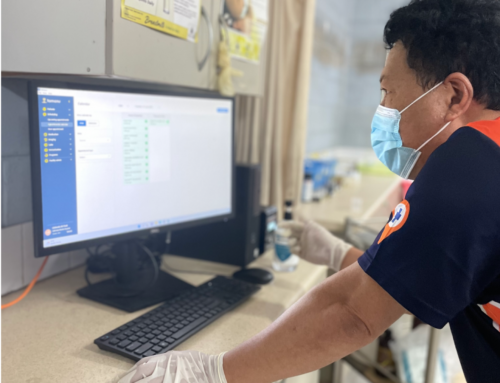

These are problems we’re trying to solve. We’re currently rolling out an NCD screening tool as part of our electronic medical record (EMR) software project, Tamanu. The aim is for nurses to go out into the community, into schools, identify people who may be at risk, and develop action plans for people to follow. From there, people at risk might follow up at their local clinic, a hospital, or a diabetes centre, for further diagnosis and treatment.

Using a paper-based system, this kind of proactive community outreach would be incredibly challenging. By using Tamanu, every professional in the person’s continuum of care will be able to access their treatment plan and update it, making sure that treatment is consistent, comprehensive and coordinated. Tamanu is also a sync-enabled system, allowing health workers to enter data (on mobile or desktop) when offline, allowing them to access patients in even the most remote settings.

Electronic medical records create more trust in the healthcare system and more willingness to engage with it

Anyone who’s ever interacted with a healthcare system in any country knows the frustration of filling out forms and giving a detailed and personal medical history, only to be referred onto another facility and asked to go through it all again. Intimate discussions of your health conditions and body can make you feel vulnerable, and it’s difficult to put yourself through it time and time again.

Beyond the sheer hassle of it, it feels like no one’s paying attention to you or putting in the effort to remember you. It starts to feel pointless and that experience is no different for people in the Pacific Islands.

If we want people to engage with the healthcare system, we have to make the experience positive for people. Electronic medical records are one way to do that. They reduce the friction and they make people feel seen, because each new healthcare professional they interact with is already familiar with their history.

Improvements to basic processes don’t attract headlines the way new drugs do, but they make a huge difference to the healthcare system and to people’s lives.

“Electronic medical records improve quality of care, patient outcomes, and safety through improved management, reduction in medication errors, reduction in unnecessary investigations, and improved communication and interactions among primary care providers, patients, and other providers involved in care.”

– Donna P. Manca MD MCLSC FCFP, Do electronic medical records improve quality of care?

This project is proudly supported by the Australian Government.